Another week went by, and the discourse and dialogue have started to kick in. Even the workload has become more stable and manageable. But exactly how does this relate to the liveliness of each group? What did I predict students would do differently from the first week? Was I able to guess it? Well, it’s complicated.

With the help of each group’s 責任者 (sekininsha, the person responsible for the team), we started to collect individual group data. But I argue it is too soon to look at those data (more on that at halfway through the project). So, we are going to dive into Slack own analytics page.

The first graph illustrates the total number of messages sent each day from the start of the project (February 2nd) to February 18th (even though this post is being written in 2/22, the latest available data go back to 2/18). Daily active members are highlighted in green, whereas the total number of messages is represented in blue. Out of 167 members on Slack, only 119 are active participants, so I shall set this number as what we should aim to achieve as for daily participation, at least on the weekdays. I ought to remember the definition of “Daily active members” according to the official Slack website, that is the “number of people who have read or sent a message in at least one channel or direct message over the current day.” I understand the difficulty of being overly talkative in a chat, which could be sometimes felt as foreign to the students. However, reading is also part of the participation in the project, this means that participant members have the responsibility of at least reading what is being said during the day. This is in fact an import objective our project ought to reach. Often described as intercultural responsibility in Applied linguistics and Communication Science fields, it is the equivalent of the philosophical concept of moral responsibility. Once again, I will refer to the easily digestible Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy to describe this concept. Moral responsibility “is concerned not with accounts that specify people’s responsibilities in the sense of duties and obligations, but rather with accounts of whether a person bears the right relation to her own actions, and their consequences, so as to be properly held accountable for them.” You can find more about the specifics of this topic applied to applied linguistics in Jackson, 2020. Moreover, “ethical dilemmas achieved through intercultural responsibility will balance relativistic and universalistic perspectives, leading to emancipatory citizenship and the “corresponding re-framing of institutions and organisations”” (Guilherme, 2010 in Ferri, 2014). For this reason, responsibility is often referred to as related to emancipatory praxis. To conclude this tangent, I believe that daily action (dialogue as both writing and reading), should be considered the central pillar of this project, thus the importance of these data.

Going back to the first graph, we can see that daily participation goes under what I hoped for after Wednesday the 12th. This is a downward trend. As of now, it does not bear any significant meaning, but it could foresee a participation problem, leading back to responsibility. Even the number of messages sent in the channels is problematic as it looks like the average is less than 1 message per person each day. Next time that I will look at the data, I will be sure to refer to this post.

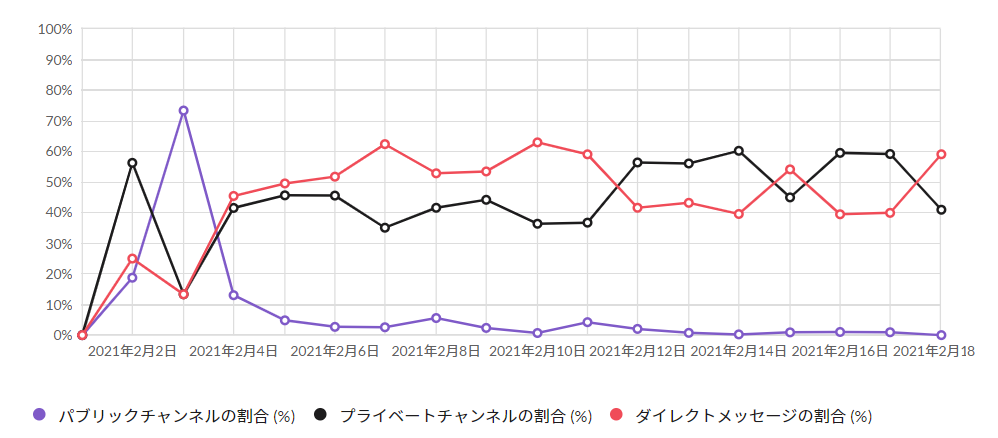

The second graph illustrates where people tend to send messages as percentage points. The purple line indicates the public channels (mainly notification from the coordinators), the black one indicates the private channels (groups channels and 自由会話 jiyū kaiwa, free discussion classroom channels), lastly, the red line indicates direct messages. Even though the graph is pretty straightforward, arises a dilemma. It is undeniable that in a democracy, private conversations ought to exist, but should they be higher than the actual public discourse? Democracy can exist only when decisions are taken by the entire group, so can it exist if half of the dialogue happens in enclosed spaces? Nevertheless, there is clearly a trend towards the public discussion (that is group dialogue), so my hope is that it will gradually go better and better.

As for now, I will stop here. I hope I was able to shed some light on the available data and my interpretation. During this week, I will try to look for implications for the coordinators. How can we foster group dialogue? Do direct messages lessen the ability to make a group decision?

References

Ferri, G. (2014) “Ethical communication and intercultural responsibility: a philosophical perspective”, Language and Intercultural Communication, 14:1, 7-23.

Guilherme, M., Glaser, E., del Carmen Méndez Garcia, M. (Eds.) (2010), The intercultural dynamics of multicultural working. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

Jackson, J. (Ed.) (2020), The Routledge Handbook of Language and Intercultural Communication (2nd ed.). London: Routledge.

Talbert, M. (Winter 2019 Edition) “Moral Responsibility”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, edited by Edward N. Zalta, https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2019/entries/moral-responsibility/ (visited 02/22/2021).

22 2月 2021 at 18:09

Thank you Leonardo for your insights about numbers and participatory responsibility. I am curious to know if writing/commenting in this blog could be perceived as a ‘substitution’ of writing into Slack Channels… could be an interesting questions to ask in a ‘mid-period survey’ for all our students! What do you think?

22 2月 2021 at 18:40

It could be an interesting data to have. I am thinking about what to do next in regard to participation. Qualitative data would compliment very well all the quantitative data that we are collecting!